Industrial additive manufacturing (AM), often called industrial 3D printing, is now a core method of production rather than just a prototyping tool. It fabricates objects layer by layer from digital designs, without tooling.

The global market for industrial additive manufacturing is valued at $21.8 billion, with use cases ranging from GE Aviation producing over 100,000 fuel nozzles to healthcare firms manufacturing 220,000 patient-specific implants daily.

The technology has tight tolerances of ±0.05-0.2 mm and build rates up to 12,000 cm³ per hour, placing it firmly within industrial production standards.

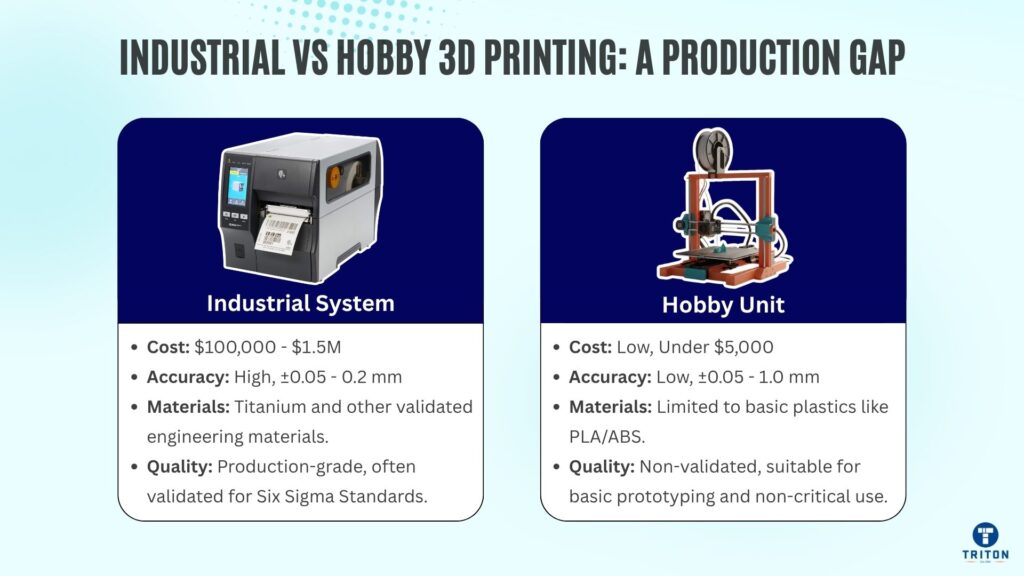

Industrial 3D printing is not the same as hobby printing. A desktop unit under $5,000 might handle PLA or ABS with tolerances of ±0.5-1.0 mm. Industrial systems, by contrast, run PEEK (Polyether Ether Ketone) with tensile strength up to 100 MPa or titanium alloys above 950 MPa, and cost $100,000-$1.5 million. They also offer validated materials, controlled atmospheres, and Six Sigma quality.

Additive manufacturing cuts tooling costs, shortens lead times, and makes low-volume runs viable. It consolidates assemblies, reduces weight, improves performance, cuts waste and on-demand local production removes supply chain risk.

By the end of this article, you’ll know when additive manufacturing makes economic sense, how the main processes and materials work, and where industries like aerospace, medical, and automotive are applying it today. You’ll also see the limits, the standards shaping adoption, and the trends defining its future.

Industrial additive manufacturing (AM) competes with injection moulding and CNC machining in cost and speed. It removes tooling costs of $5,000-$100,000, cuts lead times from months to days, and supports complex designs that machining cannot handle. However, machines cost $100,000-$1.5 million, and feedstock runs 10-20x higher than conventional materials.

AM wins in low-to-mid volume production and in complex geometries.

Injection moulding: Tooling for IM costs $5,000-$100,000 depending on cavity size and complexity. AM avoids this entirely. For a nylon automotive duct with internal lattice structures, breakeven against injection moulding sits at 250-2,000 units, because AM avoids the $50,000 tooling cost and produces the complex geometry directly. Above ~2000 units, the low per-part moulding cost outweighs AM’s tooling advantage.

CNC machining: Machining costs climb fast for parts needing multiple setups or complex internal channels, such as aerospace heat exchangers, orthopaedic implants, and automotive turbocharger housings. AM produces these directly, often in one step, lowering total production cost by removing assemblies and machining hours, even if the per-part cost of AM itself is higher.

Metal Additive vs Conventional Manufacturing: At first glance, metal additive manufacturing looks uneconomical because powder feedstock is expensive( c. $40-500/kg), while bar stock is cheaper (c. $2-10/kg).

But machining wastes most of it.

For example, a “buy-to-fly” ratio of 12:1 is standard in aerospace, which means a twelve-kilogram titanium billet is machined down to yield one kilogram of finished part. In contrast, Additive Manufacturing builds near-net-shape components with a buy-to-fly ratio as low as 1.5:1.

For low production volumes or weight-critical applications, like jet engine brackets or spacecraft mounts, Augmented Manufacturing’s lower material waste and part consolidation outweigh its higher per-kilogram powder cost.

The economics of AM has four main cost drivers: capital equipment, materials, skilled labour, and post-processing. Together, these determine when AM makes sense compared with conventional production.

Industrial printers are expensive. Polymer machines typically cost $100,000-$300,000, while metal systems run $350,000-$1,500,000. On top of this, companies need ancillary equipment such as furnaces, de-powdering stations, and safety infrastructure, adding $150,000-$600,000. This high entry cost means AM is most viable when machines run at high utilisation.

Feedstock is the most significant variable cost. Engineering polymers such as PEEK cost $450-600/kg, compared with $30-50/kg for injection-moulding pellets. Titanium powders sell for $150-400/kg, while conventional wrought stock is $20-40/kg. Even though AM uses less material overall, feedstock still makes up 30-50% of operating expenses.

Running an AM operation requires knowledge workers and operators. Engineers must prepare build files, optimise part orientation, and handle post-processing. Annual wages for these roles are $50,000-$100,000, 25-35% of the total ownership cost. Labour intensity is higher for AM because of the expertise required.

Few AM parts come out ready to use. Heat treatment costs $500-$2,000 per batch, and aerospace parts often require Hot Isostatic Pressing (HIP) at >100 MPa to eliminate porosity. Surface finishing is up to 60% of the final part cost.

In conclusion, while AM avoids tooling costs and saves on wasted material, businesses must account for high machine prices, expensive feedstock, skilled labour, and post-processing. The balance makes AM most competitive in low-volume, high-complexity production, where conventional costs escalate.

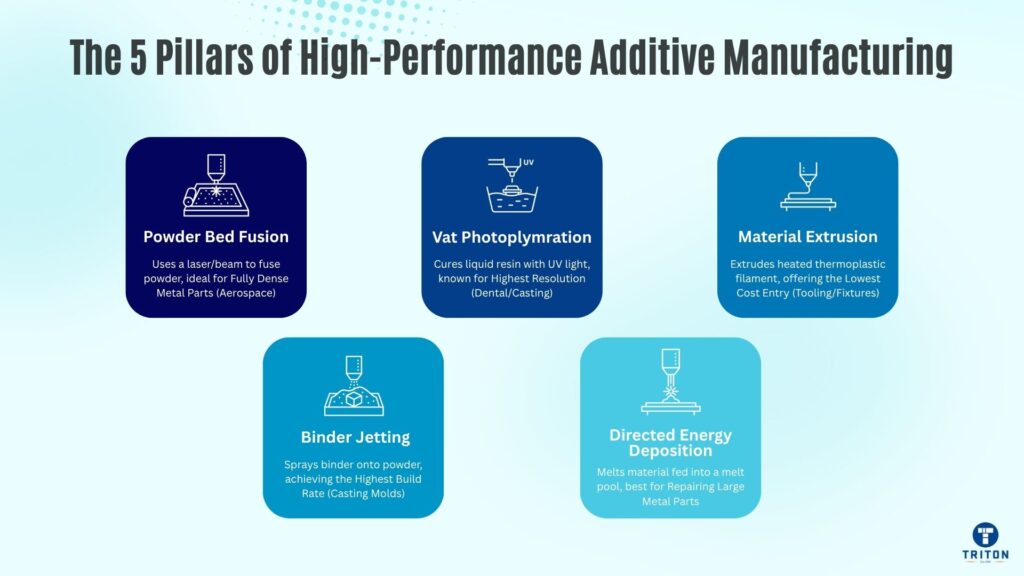

Industrial additive manufacturing is built on five core process families.

These are Powder Bed Fusion, Vat Photopolymerization, Material Extrusion, Binder Jetting, and Directed Energy Deposition.

Each delivers different trade-offs in accuracy, build speed, material compatibility, and part size, with tolerances as tight as ±0.05 mm and build rates up to 12,000 cm³/hour.

Powder Bed Fusion is a widely adopted Industrial 3D printing process for polymers and metals.

It uses Selective Laser Sintering (SLS) for polymers and Direct Metal Laser Sintering (DMLS) or Selective Laser Melting (SLM) for metals.

The process spreads a thin layer of powder and uses a laser or electron beam to fuse material in cross-sections. The cycle repeats to complete the part.

Performance metrics

Materials

Applications

Economic factors

Key advantage:

PBF produces fully dense, load-bearing parts with complex geometries that are not machinable, making it suitable for aerospace, medical, and automotive applications where volume is low but performance demands are high.

Vat Photopolymerisation uses Stereolithography (SLA) and Digital Light Processing (DLP). Both processes cure liquid photopolymer resins with a UV light source.

SLA draws each layer with a laser, curing the resin point by point. DLP projects an image of the entire layer, making it faster while achieving the same tolerance.

Performance metrics:

Materials:

Applications:

Economic factors:

Key advantage:

VPP delivers high-resolution, smooth-surface parts faster than machining can produce prototypes, making it dominant for prototyping, dental, and casting applications where accuracy and surface quality outweigh the need for mechanical strength.

Material Extrusion, also called Fused Deposition Modelling (FDM) or Fused Filament Fabrication (FFF), a widely used AM process. A heated nozzle extrudes thermoplastic filament layer by layer to print the part.

Performance metrics:

Materials:

Applications:

Economic factors:

Key advantage:

MEX is the lowest-cost entry point into industrial AM and supports a wide range of thermoplastics, making it suitable for functional prototypes, production tooling, and end-use parts where moderate accuracy and strength are acceptable.

Binder Jetting builds parts by selectively depositing a liquid binding agent onto a powder bed, layer by layer. The bound part is cured, followed by infiltration or sintering to reach the final strength.

Unlike Powder Bed Fusion, no lasers or heat sources are used during the build, which makes the process faster and often cheaper at scale.

Performance metrics:

Materials:

Applications:

Economic factors:

Key advantage:

Binder Jetting has higher throughput and lower material cost than PBF, which makes it suitable for casting moulds, metal parts in medium volumes, and large-format sand applications where speed and cost per unit matter more than density.

Directed Energy Deposition uses a focused heat source, usually a laser, electron beam, or plasma arc, to melt material as it is deposited. Material is fed as powder or wire into the melt pool to build or repair parts layer by layer. The process is sometimes integrated into robotic arms or CNC machines for hybrid manufacturing.

Performance metrics:

Materials:

Applications:

Economic factors:

Key advantage: DED excels at building or repairing large metal parts at a lower material cost than powder processes. It is best suited for aerospace, defence, and energy industries where part size, repairability, and material savings justify the investment.

Process | Accuracy/Tolerance | Build Rate | Build Volume | Material Costs | Machine Costs | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Powder Bed Fusion (PBF: SLS, DMLS, EBM) | ±0.05-0.2 mm (DMLS to ±0.05 mm)

| 5-171 cm³/hr (multi-laser up to 100x faster) | Up to 400 x 400 x 400 mm | Metals: $50-400/kg; Polymers: $50-100/kg | $350k-$1.5M | Aerospace turbine blades, fuel nozzles, orthopaedic implants, lightweight brackets |

Vat Photopolymerization (VPP: SLA, DLP) | 25-50 microns, ±0.15%

| Up to 100 mm/hr | ~353 x 196 x 350 mm | Resins: $150-400/L | $100k-$300k | Dental aligners, surgical guides, hearing aids, moulds, appearance prototypes |

Material Extrusion (MEX: FDM/FFF) | ±0.127-0.3 mm | Up to 91 kg/hr (BAAM) | Up to 6 x 2.4 x 1.8 m | Polymers: $30-600/kg; composites with carbon/glass fibre | $100k-$300k | Aerospace tooling, jigs/fixtures, automotive prototypes, large composite parts |

Binder Jetting | ±0.1-0.3 mm | Up to 12,000 cm³/hr | 750 x 330 x 250 mm (Desktop Metal P-50) | MIM powders: $20-100/kg | $250k-$1M + furnace ($150k-600k) | Automotive brackets, sand casting moulds, batch metal parts, legacy parts |

Directed Energy Deposition (DED) | ±0.3-0.8 mm | 10-200 cm³/hr (wire-fed up to 9 kg/hr) | Metre-scale (no chamber limit) | Wire: $20-50/kg; Powders: $100-300/kg | $500k-$2M | Large aerospace structures, turbine blade repair, defence/naval propellers, hybrid AM-CNC builds |

Industrial additive manufacturing must deliver accuracy of ±0.05-0.2 mm, repeatability at Six Sigma levels, and tolerance control that matches aerospace and medical requirements. These targets are measured in four areas: accuracy, repeatability, real-world tolerances, and process monitoring.

AM delivers precision suitable for critical industries, but only when coupled with process control, validated machines, and standardised parameters.

AM parts require post-processing to achieve strength, surface finish, and certification standards. The steps vary by process and material, typically including support removal, heat treatment, HIP, and surface finishing.

Post-processing adds time, cost, and labour to every AM build. In many cases, post-processing accounts for 30-60% of the total part cost, making it a critical factor in assessing AM’s business case.

Material Class | Examples | Tensile Strength | Heat Resistance | Cost Range | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Polymers | PA11, PA12, ABS, PC, PEEK, PEKK | PA12: 48 MPa; PC: 70 MPa; PEEK: 95-100 MPa | PEEK/PEKK: 250-300 °C; PC: 140 °C | $30-50/kg (PA12); $450-600/kg (PEEK/PEKK) | Aerospace ducting, medical implants, automotive housings, tooling |

Metals | Ti6Al4V, Inconel 718, 316L, AlSi10Mg, CoCr | Ti6Al4V: 950 MPa; Inconel 718: 1,250 MPa; 316L: 570 MPa | Ti6Al4V: up to 400 °C; Inconel 718: up to 700 °C | $150-400/kg (Ti); $50-100/kg (steel) | Jet engine parts, orthopaedic implants, structural brackets, tooling inserts |

Ceramics | Alumina, Zirconia, Silicon Carbide | Alumina: 300-600 MPa; Zirconia: 900-1,200 MPa | Up to 1,600 °C | $20-100/kg powders | Dental crowns, heat exchangers, electronics, aerospace insulators |

Composites

| Nylon + carbon fibre, ULTEM + glass fibre, thermoset composites | Tensile strength up to 200-250 MPa (carbon fibre reinforced) | 150-250 °C depending on matrix | $100-300/kg filaments | Lightweight tooling, UAV components, automotive brackets, jigs/fixtures |

Industrial additive manufacturing requires recognised standards to qualify parts for aerospace, medical, and automotive use.

Certification ensures AM parts achieve the same safety and reliability as conventionally manufactured parts. Without compliance with ISO, ASTM, and industry-specific standards, industrial applications cannot use 3D printing.

High capital and material costs, slow build rates, limited volumes, quality variability, and integration challenges hold AM adoption back. The technology is best applied today to low-volume, high-complexity, high-value parts. Broader use will have to wait for the development of faster machines, cheaper feedstocks, and seamless workflow integration.

High upfront cost is the main barrier. Industrial polymer systems cost $100,000-$300,000, while metal systems cost $350,000-$1.5 million. Ancillary equipment like furnaces, de-powdering stations, HIP systems, and safety infrastructure can add $150,000-$600,000 to the setup. This makes adoption capital-intensive compared with conventional CNC or moulding.

Material limitations are another hurdle. Engineering polymers such as PEEK cost $450-600/kg, compared with $30-50/kg for injection-moulding pellets. Titanium powders cost $150-400/kg, versus $20-40/kg for wrought stock.

The workforce requirement is also steep. Running an AM cell needs engineers for design, build file preparation, and post-processing. Skilled AM engineers are in short supply, making labour a capacity bottleneck.

Build speed and volume are slower than conventional manufacturing.

Defect detection and inspection add more delays. Computed tomography (CT) scans with ±13 µm accuracy are used for high-value parts, but CT machines cost over $1 million, and with scans that take hours, throughput is low. In-situ monitoring reduces risk but does not eliminate the need for destructive or CT testing.

Integrating AM into established production systems is difficult. Most firms design parts for casting or machining, not layer-by-layer builds. This creates the need for design for additive manufacturing (DfAM) skills, including topology optimisation and lattice design, which many teams lack.

Quality management is also a sticking point. Aerospace parts should follow AS9100 and ASTM AM-specific standards, while medical parts should comply with ISO 13485 and FDA guidance. Each build must be validated with witness coupons or CT scans, adding time and paperwork compared with conventional machining certifications.

Post-processing steps complicate the workflow further. Heat treatment, HIP, machining, and polishing extend lead times, adding 30-60% to part cost, which blunts the speed advantage of printing, especially for high-value metal components.

Finally, supply chain integration is incomplete. Few ERP or MES systems handle AM-specific data such as layer monitoring, powder recycling rates, or lattice structure validation. Firms often run AM as a siloed operation, disconnected from mainstream production flows.

Today, industrial 3D printing delivers ±0.05 mm accuracy, supports metals, polymers, and composites, and produces qualified aerospace and medical parts at scale. It is used in assemblies, has cut up to 90% of waste, and enables on-demand spares. These capabilities form the baseline for what comes next.

The future lies in faster build rates, lower-cost feedstocks, and fully automated production lines, integrating AI-driven design with end-to-end quality control. Distributed manufacturing hubs will replace centralised warehouses, with digital inventories enabling on-demand, local production.

As standards mature, adoption will scale further.

Visit Triton Store to explore the tools and technologies that prepare your business for this shift.